1: About the exhibition “Above Ground”

Oyama:

You have curated 2 exhibitions at the Museum of the City of New York, “City as Canvas” in 2014, and “Above Ground” that is currently on view. Both exhibitions are based on the Martin Wong collection, the infamous collection of street art works and related materials from 1970s and 80s New York, which were donated to the Museum from Martin Wong in 1994. Would you please start by describing the difference between those 2 exhibitions?

Photo ©︎LGSA by EIOS

Corcoran:

The first show, City as Canvas, was really about reorienting the public’s understanding of New York graffiti and street art. At the time—this was about 10 years ago—public perception of graffiti was largely negative. Most people saw it as vandalism committed by kids randomly damaging public spaces.

The idea behind City as Canvas had two main goals. First, to shift the general public’s perception of who graffiti writers were in New York during the 1970s and 80s, and what their intentions were. Second, to present the major collection of graffiti art acquired and preserved by Martin Wong, which he later donated to the Museum of the City of New York for future research and exhibition.

The exhibition aimed to portray graffiti writers as serious artists and to explore the various motivations that led them to the streets. Some had significant artistic ambitions, while others participated more casually. That range of intentions came through in City as Canvas. Some artists transitioned into lifelong studio practices, while others were active on the streets for only a short time. In the exhibition, you could see them side by side in the black books—some even experimented with canvas, though they never fully transitioned to studio art. We also included many photographs of street art by Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant, which helped provide a broader context of what was happening in New York at the time. In contrast, Above Ground focuses on artists who started on the streets and then transitioned into galleries and studio practices.

One long wall in the exhibition (Above Ground) acts as a kind of shorthand for that movement, starting in the 1970s with the United Graffiti Artists (UGA). We didn’t include the Nation of Graffiti Artists (NoGA), but they could easily have been the next chapter.

Photo ©︎LGSA by EIOS

Instead, we move forward to the Esses Studio in the 1980s, then tell the story of the East Village gallery scene—beginning with small non-profit spaces like Fashion Moda, then moving to indie commercial galleries like Fun Gallery and 51X. We also touch on the point when mainstream galleries like Sidney Janis, Barbara Gladstone, and Tony Shafrazi began showcasing these artists, giving them broader exposure to the art world.

There are two small feature sections in the gallery. One highlights Tracy168. We show a photograph of one of his early train pieces from around 1974, then a sketch he made at Esses Studio in 1980, followed by a photo of him with canvases at the Above Ground gallery. This sequence tells the story of his transition from street art to a more formal studio practice.

Another great example is Lee Quiñones. Around the corner, we show his original sketch for The Art of Doomsday—a figure in a train yard. Then there is a thumbnail image of the painted train featuring that figure. In a display case, we show materials from his first show in Italy in 1979 at the Medusa Gallery, including a painting he made for that exhibition, though it wasn’t illustrated in the catalog. There’s also a photo of him with Lady Pink at the New Museum in 1981, where he painted a mural for their exhibition. These elements together illustrate how ideas originating on the streets made their way into galleries.

Photo ©︎LGSA by EIOS

As visitors move further into the exhibition, they encounter works created specifically for galleries. You can really see the diverse paths these young artists took. One section is arranged to echo Martin Wong’s Museum of American Graffiti. If you take the detour to the section about Martin, you’ll see installation photos that we echoed in the layout of Above Ground.

The main focus here is on canvas-based work, which highlights the various artistic styles and methods that emerged in those early years. For example, Futura 2000 began moving toward abstraction in 1980 and still uses some of those techniques today. Crash was heavily influenced by pop art—Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein—and that influence is immediately apparent. To the left, there is work by Haze, who was very interested in graphic design. You can see his focus on geometry and visual arrangement. Lee’s work, on the other hand, is more narrative and figurative, telling stories through painting. Then there are collaborations, like those between LA2 and Keith Haring, which also appear in the exhibition.

Daze, for example, his works in particular show a clear transition from working with letterforms to exploring figuration. Other artists retained letterforms in their work, but they took on new and different forms. For instance, there is a long piece by Delta 2 near the bottom, which looks like it could have come straight off a train—it resembles a “between doors” panel, a “window-down” piece.

Above it, there is a work by Sharp, who was Delta 2’s partner on trains for a long time.

Sharp took those same letterforms and pushed them in a very abstract direction. Then next to that, you have A-One, who created very delicate, psychedelic linework. And next to that is Dondi. He still worked with wild style lettering, but he was also incorporating figurative elements, like alien or robot-like characters. Then, there is Quik, whose work still looks very much like what you’d expect to see on a train.

Photo ©️LGSA by EIOS

When you look around the room, you can really see all the different approaches—how each artist explored being a studio artist in their early years, while still employing spray can techniques developed on the street. That’s really the point of this section.

Oyama:

So the main half of the gallery is designed to show the variety of artists and techniques that were emerging during that time.

Corcoran:

Exactly.

2: The Role of the Museum of the City of New York

Oyama:

Because this is the Museum of the City of New York, I assume one of the missions is to show the legacy of New York City—mainly to New York residents, perhaps?

Corcoran:

Yes, that’s right. Part of what makes this collection so appealing to us as an institution is that graffiti is arguably a New York-born art form. Maybe you could give some credit to Philadelphia, too—but really, this is a New York culture.

And actually, this could become the basis for a third exhibition. You’d have the first show focused on what was happening on the streets, the second—like this one—on the transition to the studio and so-called “legitimate” art spaces. The next step could

What happened after that?

Because from here, the work—and the culture—started being exported to the rest of the world. You had Subway Art, the book, and films like Wild Style, Style Wars, and Beat Street. These all came out of this culture and helped spread it globally. We even acknowledge that moment in the gallery. There is a section showing invitations to museum shows in Europe and early gallery exhibitions overseas. This was the point where New York’s graffiti culture became a global phenomenon.

Haze, for example, became a graphic designer and created logos for some of the biggest names in Hip Hop. He also did product and apparel design seen around the world. Futura 2000 designed sneakers. So, this exhibition captures the stage just before—or right in the middle of—the culture’s explosion into global visibility. That’s a big part of why this show is so interesting for us: because today, many of these artists are internationally recognized figures in the evolution of this art form.

Oyama:

Yes, exactly—that is one of the things I was thinking about.

Meanwhile, I would also like to ask: while this show focuses on the transition from street to studio practice or gallery exhibitions, it is not just about commercial success, right?

Corcoran:

Right. It’s more than that. Considering the nature of the museum and our audience, the goal is not simply to show that these kids became commercially successful. It is to show that they were serious artists—people pursuing their own subjects, their own visions. It wasn’t just about causing a public nuisance.

Oyama:

Exactly.

Corcoran:

In reality, the artists featured in this show represent maybe only 10 to 15 percent of all the kids who were out writing on the streets. They are the ones who took it to the next level.

Oyama:

So, the number of artists included in Above Ground is smaller than in City as Canvas.

Corcoran:

Yes, that’s right.

3: Street art and its dual reality

Oyama:

Going back to something you mentioned earlier—about how you had to consider the public perception in the ’70s and ’80s when you did City as Canvas. At that time, people viewed graffiti culture negatively. That memory is not entirely gone, is it?

I was born in 1983 and grew up in Tokyo. When I was in high school around 2000 or 2001, I got to know street art through magazines and the internet. By that time, it was already being presented as an art form. I wasn’t around during its origins, so I didn’t experience the more negative perception. There is this generational duality—some people still associate it with negativity, while others see it as something artistic. The former tends to be older generation than the latter, I assume.

Corcoran:

It tends to be generational. People who were adults in the 70s were living through a city in fiscal crisis. It was a really bad time for New York—people were leaving, buildings were being abandoned in the Lower East Side and the South Bronx. Some buildings were being burned down.

The city government did not have enough money to provide services like fire departments and garbage pickup for all neighborhoods. There was something called “planned shrinkage.” It gets deep quickly, but basically, the city was in really bad shape.

So, for many people, the lawlessness of youth—just being out there doing whatever they wanted, and in many eyes, destroying public property—became a symbol of chaos, of the city failing to maintain order. That is the negative association.

At the same time, there were people praising what was happening, saying there was real creativity here that should be fostered and encouraged. There was a duality of public attitudes.

Someone like Richard Goldstein from The Village Voice, or even artists like Claes Oldenburg or writers like Norman Mailer, they saw the beauty in what was happening. But on a day-to-day level, for people riding the trains—even if they liked the big masterpieces on the outside—once they got inside, it was covered in ink. You didn’t know if you could sit down, or if you were going to get ink on your suit or something. So, you can see why people had mixed feelings about it. Younger people were very interested in it. Martin, who moved to the city in the late 1970s, was obviously very attracted to it.

Oyama:

I’m guessing that type of duality was probably a very specific condition to New York at that time.

Corcoran:

I can speak to Europe, but I don’t know about the rest of the world—but in Europe, they’re still trying to keep graffiti writers off the trains, off the transit systems. There is still this tag-of-war between municipal bodies, governments, and the artists who are trying to express themselves. That is still going on. Even here, people still come and paint trains—they just clean them off before they ever really run. They are still prosecuting people when they catch them—not just here but in Europe as well. So, the tension still exists. But for the general public, there is a lot more tolerance now—ranging from tolerance to acceptance, even encouragement.

In 1980, if you walked around the street and asked what people thought about graffiti, the negative association would be more than 50%. Today, it could be 30%—maybe even 20–30%. I think a lot of that has changed because many of these artists have done incredible things over the years. People have bought their T-shirts, their sneakers. They have come to admire and appreciate what’s been done. That has changed people’s outlook on the artistic output that originated in the streets. As generations move and change, it becomes more accepted, more commonplace—and even inspirational.

Oyama:

The media environment has also changed. Subway cars were the main platform back then—that was the way artists circulated their works among the public. But now we have the internet, SNS… there are different ways to spread the works.

Corcoran:

There are more and more opportunities for permission—to do it on walls, beyond just commercial products. More places are interested in having artists work on their walls, in public spaces. However, back then, there were articles like “Fight Against Graffiti Progresses From Frying Pan to Fire”—meaning it is getting worse. You had Boy Scouts scrubbing trains, kids getting caught and sentenced to public service. Eventually, Mayor Koch wanted to fence in the train yards and have them patrolled by dogs.

Subway graffiti was called an epidemic. That was the language—an epidemic. It was something sick, out of control—like a pandemic. And here you see the early efforts—they were cleaning the trains. One article talks about how they painted all the cars white at one point. They tried to give them a clean slate—but then, of course, tags started appearing again. It became like a blank canvas. So yeah, it was considered a public nuisance by many people at the time.

Oyama:

Did you collect this yourself?

Corcoran:

Some of these I collected myself, and others we had in our clipping files—things like that.

Oyama:

Pretty amazing.

Corcoran:

So, crime was increasing in the subways, and the visual association of random tagging and a sense of lawlessness became conflated. This gives you a sense of how the media at the time—talking about how perceptions have changed—was almost entirely negative in the 70s and early 80s, except for very few outlets like The Village Voice.

Photo ©︎LGSA by EIOS

4: “Graffiti” and “Writing

Oyama:

What do you think of the term “graffiti”—because back then, the writers used to call themselves “writers,” right?

Corcoran:

Right. “Graffiti” was a name put on it by the media. If you talk to someone like Phase 2, he would never use the word “graffiti.” He called himself an “aerosol artist” or a “style writer.”

Oyama:

I’m kind of influenced by Phase 2’s perspective to some extent. But at the same time, I think at some point, even artists themselves started using the term “graffiti.” I am not sure when that turning point was.

Corcoran:

Yeah, it became shorthand. People knew what you were talking about. It may not align with the literal meaning of “graffiti”—which is to scratch or scrawl—because they didn’t consider what they were doing to be that. They saw it as writing—artistic writing. But when that is how the general public understands it, you eventually start using it too. Personally, when I talk to people, I do not usually say “graffiti artist”—I will say “writer” or “aerosol artist.” But “graffiti art” has become the commonly understood term.

Oyama:

So at some point, insiders in the culture started using the term too, just because it’s easier. It became shorthand. But that was a turning point. The term “graffiti” carries such a strong negative association—often linked with crime. If they had stuck with calling it “writing,” maybe history would’ve evolved differently.

Corcoran:

Right. But “writing” is vague—everyone writes, even if they’re not a style writer. So, unless you’re an insider, the term almost becomes meaningless. If early on they had been called “style writers” or “aerosol artists,” that might have stuck. But because “graffiti” was used so predominantly in the first 10 years, it became really hard to shift the language. As much as people like Phase 2 tried, it was too difficult to change. Even now, in our subtitles, we say “graffiti art,” and I kind of hate it—but it is the term everyone understands.

Oyama:

It has already been spread and been generalized.

Corcoran:

It is part of popular culture, part of mass culture now.

5: To Write History

Oyama:

Last question—Exhibitions like City as Canvas and Above Ground could be regarded as an attempt to establish a historical narrative of street art or aerosol writing. In that sense, 1970s and 80s New York is almost the only perspective to start that narrative.

Corcoran:

Absolutely.

Oyama:

From the 90s onward, there could be different perspectives—maybe European ones. From around 2000, I would say Japan also began having a relationship with New York. There are a few museums and curators trying to establish the history of aerosol writing and street art. How do you differentiate your curatorial practice from other museum projects?

Corcoran:

That is a great question. From a personal perspective, I think that negative association with graffiti has persisted for a long time—especially within art museums. Not all, but many. That is changing now. From the time we did our first exhibition 10 years ago to now, there have been many more museum shows, and the general level of acceptance is different.

But for many years, that negative association held institutions back from giving the genre serious consideration. In my mind, graffiti is one of the truly American cultural forms that the U.S. has shared with the world—rather than absorbing other cultures. I see it as similar to jazz—something genuinely American that the world has come to appreciate. It has an art history that is largely unexplored and unwritten, and there is real room for serious scholarship.

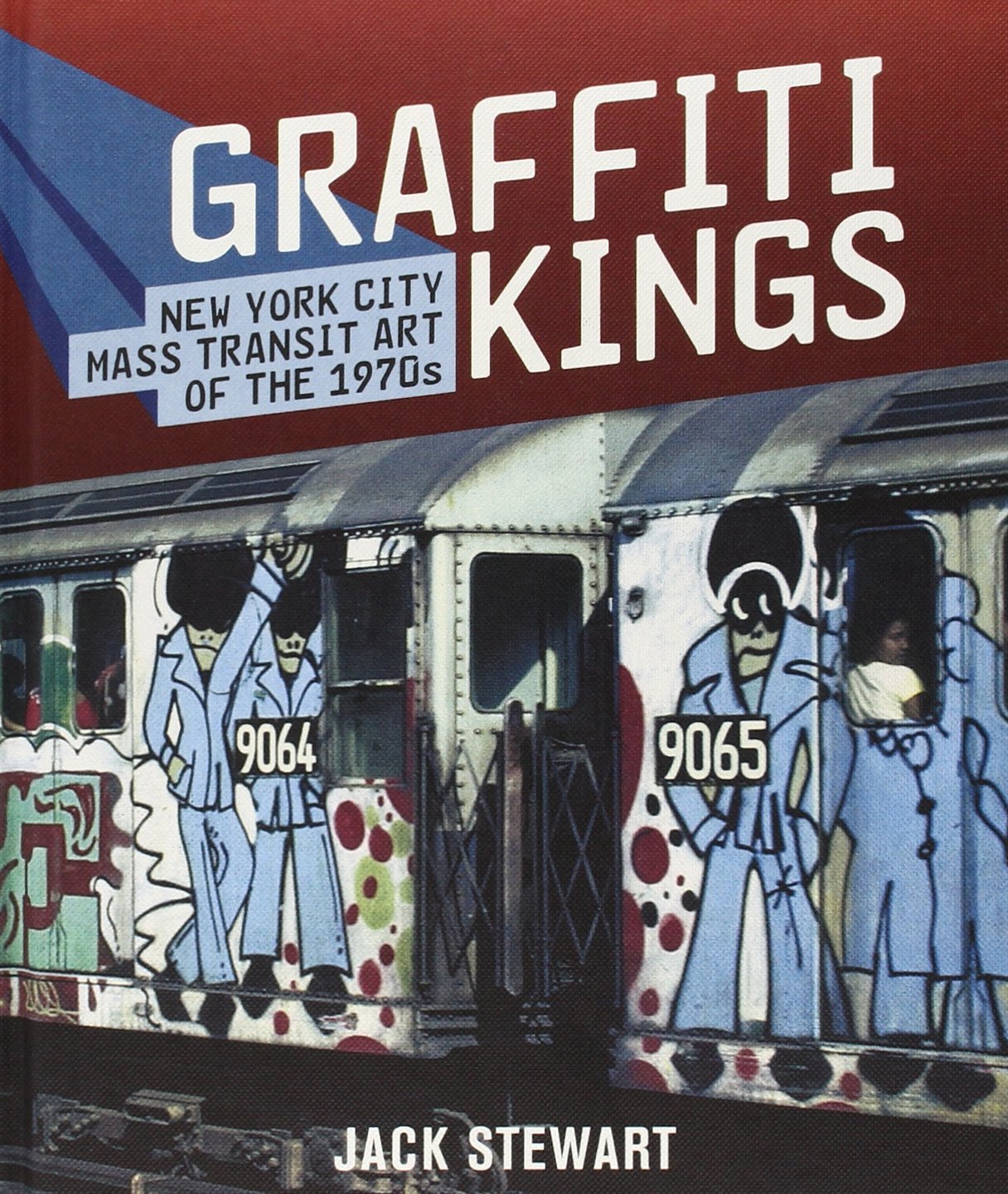

There were early pioneers, like Jack Stewart, a photographer and art historian, who started this kind of work in the 70s. And others wrote serious books—like Craig Castleman’s Getting Up, or Taking the Train by Joe Austin. In the 80s, there were some serious European catalogues, like Arte di Frontiera in Italy, which approached it from an academic angle.

There have been fits and starts, but not many people have pursued this history over the long term. Part of the problem is that large, respected institutions were slow to embrace the medium. If MoMA had gotten involved early and taken it seriously, many other institutions might have followed.

But fortunately, people like Roger Gastman and Beyond the Streets are now producing serious books and doing in-depth historical research. So yes, I do think a real art historical narrative is starting to take shape. When you look at books like Wall Writers, the Gordon Matta-Clark book, or Jack Stewart’s photographs, you start to see a development of styles—an art history of style writing in the streets.

By the 1980s, with books like Spraycan Art by Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff, you can start to see a national and even global expansion of the art form. As that happens, new and different styles are being brought into the field. So, there is a real art history—a development of style—and a kind of branching off of styles depending on where you are in the world. That is what we need to do more of. It’s finally starting to come together, piece by piece.

Oyama:

100% agree. I’m really excited that we live in an era where it is finally happening. While we were not there in New York in the 70s and 80s to be a part of the golden age itself, we could be a part of the time to historicize the golden age.

Corcoran:

Yeah, to Roger Gastman’s credit—and to a few other people as well—the participants of the ’70s and ’80s are still around. They’re starting to pass, but now is the time. It is really important to go back, talk to these people, and get their histories down. There are people out there doing this work, which is absolutely critical, because in another ten years, a lot of those founding fathers—and mothers—will be gone.

Oyama:

It is a big project, and for sure, there are a lot of different perspectives and opinions.

Corcoran:

I think that is healthy. We can get all of those opinions down—that is most important. Maybe we will form our own opinions about those opinions, but what matters is that they are documented. So, in another decade—or 20, 30, 40 years—people will be able to go back and read what everyone thought, the people who were actually taking part. As things continue to grow and change, there will be new ways of seeing those perspectives. We are in a critical moment right now. Those early generations—those guys are in their 60s, some almost 70. If they are not recorded now, it will all be lost.

Oyama:

I think you are in the best position for that because you have access to the New York originators as well as public institutions.

Corcoran:

Yeah, myself—and also a couple of folk art and folklore collections—are doing audio interviews. Some of the Queens Library, the Bronx historical societies—they are doing oral histories. City Lore downtown—they are out there doing it too. That is going to be really important for us. And someone mentioned Jack Stewart—he did audio interviews back in the 1970s.

So, now we are talking about primary source material that is starting to go into archives, like the Archives of American Art and places like that. That is where we will be going to do research, and hopefully, tell the story in a more thorough way.

Oyama:

Great. Amazing.

Corcoran:

It’s a lot of work. No one can do it all, but those of us who are serious—we all have to do our part.

Oyama:

That is going to be the foundation of the historical narrative. Then we just keep building on top of that, I guess.

Profile

Sean Corcoran

Sean Corcoran is the Senior Curator of Prints and Photographs at the Museum of the City of New York. He previously served as Assistant Curator of Photography at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY. His exhibitions have included Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick Photographs, Brooklyn: The City Within: Photographs by Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb, the current Above Ground: Art from the Martin Wong Graffiti Collection. He has written extensively on photography and graffiti, contributing to more than two dozen publications, including essays for City as Canvas, Graffiti Art from the Martin Wong Collection (Skira Rizzoli), Elliott Erwitt: At Home and Around the World (Aperture), and I See a City: Todd Webb’s New York (Thames & Hudson), Loisaida: Street Work 1984-1990 by Tria Giovan (Damiani) and has edited an upcoming publication on the photography of Robert Rauschenberg due in the summer of 2025.